Private Robert Arthur Coxon of the 8th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders was my great-uncle. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records the date of his death as Sunday, 25th September 1915 – the first day of the Battle of Loos. He was 24 years old.

Robert Arthur Coxon. Captured at the Battle of Loos, 25th September 1915.

We know, because someone close to our family saw it happen, that Robert was – in fact – captured by German troops on that day. But, his body was never found and he was never seen alive again by anyone who knew him.

This story has fascinated me since I was boy. He was caught up in a German counter-attack and was isolated. Despite his mates “knocking off five or six” of the enemy who were closing in on Robert, he was eventually overwhelmed. As he was led away to the German lines, he turned to his own lines, smiled, waved and….well, we don’t know.

So where – exactly – was he captured? Who were the troops who took him away? If he was murdered by those troops, what were the circumstances? Or could he have been caught up in a British bombardment – a victim of friendly fire while he was in unfriendly hands?

Robert was part of the first wave of British soldiers in the 44th Brigrade of the 15th (Scottish) Division to attack the German trenches at Loos, in Flanders. The attack was preceded by a 40 minute release of smoke and chlorine gas, the first time the British had used the weapon. 5,000 cylinders of the stuff – each 6 feet long and weighing 150 pounds were used.

Robert's rosary. Given to him by his Catholic fiancee. She never married.

The reason for the use of the gas was twofold. Firstly, there wasn’t enough artillery available of the right type to mount a sufficiently heavy bombardment. Heavy guns were needed, big howitzers with a high trajectory that would land a high explosive shell directly into a trench or fortification. Instead, we had smaller field guns – 18-pounders – that fired shrapnel. These were useful for wirecutting, but only where the wire could be seen easily by spotters and adjusted for effect.

Another problem was the availability of shells. British weekly production levels (22,000) were very low compared to French and German output (100,000+). This meant that any bombardment would be limited by the stocks of ammunition available.

Neither Haig (in charge of the First Army, tasked with the attack) nor Sir John French (overall commander of the British Expeditionary Force – BEF) actually wanted to launch an attack.

In fact, the considered view of the British military was that Loos was “unfavourable ground” for an attack. It was a mining district, very flat, but littered with slag heaps and pithead towers. In other words, hardly any cover but lots of vantage points for defenders.

The French army under Joffre, however, was planning a major offensive and wanted the British to provide a large-scale diversion. Lord Kitchener, head of all British forces, changed his position from opposition to British involvement to supporting it – but not out of any love of the French attack plan. Kitchener’s main concern was that the Russians – suffering badly on the Eastern Front – would withdraw from the war if they could not see action being taken by their British and French allies in the West.

So, reluctantly, the British made their plans. Gas became a decisive factor in the battle plan after Haig saw a sucessful demonstration of its use. In his eyes, the weapon that the Germans had used to good effect some months earlier, would compensate for the lack of artillery support.

At 5.50am on the morning of the attack, the attacking formations were in their starting positions, ready for the assault.

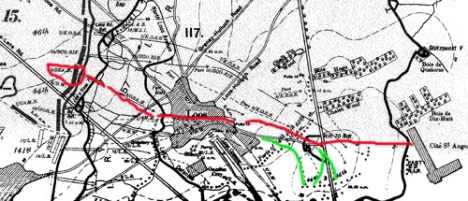

The British attack. The red line shows the starting position and intended attack route of the 8th Seaforths. The green lines show where some - including Robert - actually attacked.

The gas was unleashed. In some places it was blown gently towards and into the German trenches. In other places, it stayed in no-man’s land. And in others – as in the case of the 8th Seaforths – the gas drifted back into the British trenches. The gas attack, mixed with smoke shells, lasted for 40 minutes – 10 minutes longer than the effective working life of a German gas mask.

At 6.30am, wearing respirators, the British left their trenches and headed for the German first line. Robert’s sector – the 15th (Scottish) Division – were to experience the most successful advance of the day.

The first German line was taken within 15 minutes at the cost of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomson, all four of the Seaforth’s company commanders and about 100 other casualties.

Rushing forward, the Seaforths and the 9th Black Watch pursued the fleeing Germans into the village of Loos before the garrison there had time to mount a strong defence. The village was the scene of vicious and often unrestrained fighting. many German prisoners were ruthlessly killed and the bayonet was freely used. You get some flavour of it all from this eyewitness account.

Leaving Loos, the troops – including Robert – moved onto their next objective, Hill 70. By this time, many of the regiments were intermingled. As many of their officers were casualties by now, there was also a lack of leadership on the ground.

Hill 70 fell quickly as the German defenders saw that the oncoming British troops had made short work of both the German front line and the Loos garrison and fled towards their second line defences at Cite St. Laurent.

Robert was with a group of around 500 or so troops who chased the Germans down the hill towards Cite St Laurent. In fact, they should have continued their advance towards their original objective of Cite St Auguste.

The wire in front of Cite St Laurent was up to 15 feet thick in places. And the line was protected by a fortified strongpoint – the Dynamatiere. By the time Robert and the other troops reached the German line, they were trapped by fire from the strongpoint and from the German lines ahead. They dug scrapes in the ground for shelter and waited for reinforcements.

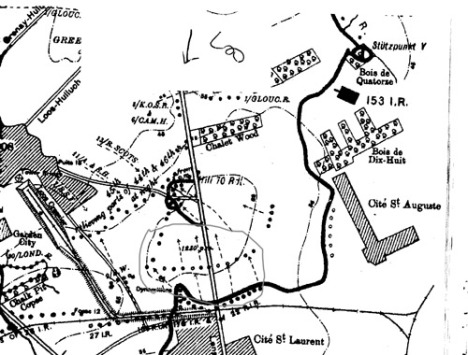

Around 12.30pm to 1pm. The German lines at Cite St. Laurent. The last place that friendly eyes saw Robert alive.

But, up on Hill 70, the few officers remaining saw that something had gone wrong. The artillery was continuing to pound the original objective of Cite St. Auguste and offering no support to the beleaguered troops in front of Cite St Laurent. The promised reserves who were supposed to be ready to pour in behind the 15th (Scottish) Division and force a breakthrough, had not arrived in time to take a useful part in this first day of the battle.

By around 12.30pm, Robert and the other troops with him were low on ammunition and were looking for a way to get back to Hill 70. Some made a break for it when the Germans launched a counter attack. Seeing the Scots run encourage more Germans to join in the assault.

It was around this time that Robert was seen to be captured.

Of the 500 British troops trapped in front of Cite St. Laurent, the Germans reported that only 50 were taken prisoner unwounded.

The troops who captured Robert were from 117th Infantry Division, largely recruited from Silesia. The troops directly opposite Robert were largely from the Division’s Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 22, supplemented by troops who had fled both from Hill 70 and Loos. These are the troops who, probably, captured Robert during their counter-attack on Hill 70. And some of these troops, at least, would have seen how some of their comrades had been slaughtered in Loos.

On 23rd April, 1917, the Australian newspaper The Hobart Mercury carried this report:

“The Amsterdam correspondent of the “Daily Chronicle” says he has obtained from a reliable source the statement of an educated German deserter as to the shooting of British prisoners. … 200 British soldiers who were taken prisoner at Loos were sent to Frankfort, but only 80 arrived, the remainder being shot.”

I don’t know whether or not this report – written in wartime – has any credence or any relation to the fate of my great-uncle Robert. All I know is that – all these decades later – by researching his story I have felt myself drawn closer to a man whose rosary beads I touched today and whose photograph I scanned for this post.

Rest in Peace, Robert.

The cemetery at Dud Corner, Loos. Robert's body was never found. His name is listed among the missing.

In looking into Robert’s story I used these research sources:

Loos, 1915 by Nick Lloyd, published by The History Press.

Loos, Hill 70 by Andrew Rawson, published by Pen & Sword Books.

History of the First World War by Liddell Hart, published by Pan.

The Fifteenth (Scottish) Division 1914-1919, J. Stewart & John Buchan, Naval & Military Press

Histories of the 251 German Divisions of the German Army, USAEF, London Stamp Exchange Ltd.

War Diary of the 8th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders, National Archives.

Most Unfavourable Ground, by Niall Cherry, published byHelion & Company Ltd.

The Battle of Loos, by Philip Warner, published by Pen & Sword Books.

British Official History, Military Operations, France & Belgium 1915, published by Battery Press.

Filed under: History, Stoke-on-Trent | Tagged: 15th Division, Battle of Loos, Hill 70, Longton, Robert Arthur Coxon, Seaforth Highlanders, Seaforths, September 25th 1915, WW1 | Leave a comment »